2023’s Nobel Prize was awarded for studying physics on tiny, attosecond-level timescales. Too bad that particle physics happens even faster.

One of the biggest news stories of 2023 in the world of physics was the Nobel Prize in Physics, awarded to a trio of physicists who helped develop methods for probing physics on tiny timescales: attosecond-level timescales. There are processes in this Universe that happen incredibly quickly — on timescales that are unfathomably fast compared to a human’s perception — and detecting and measuring these processes are of paramount importance if we want to understand what occurs at the most fundamental levels of reality.

Getting down to attosecond-level precision is an incredible achievement; after all, an attosecond represents just 1 part in 10¹⁸ of a second: a billionth of a billionth of a second. As fast as that is, however, it isn’t fast enough to measure everything that occurs in nature. Remember that there are four fundamental forces in nature:

- gravitation,

- electromagnetism,

- the weak nuclear force,

- and the strong nuclear force.

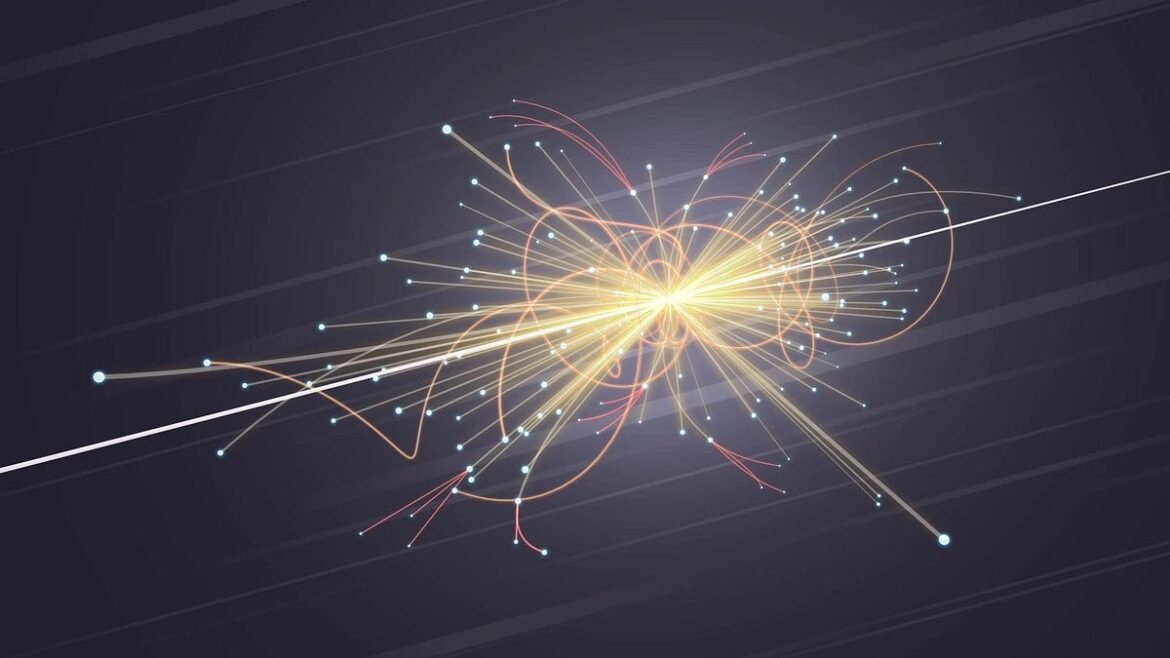

While attosecond-level physics can describe all gravitational and electromagnetic interactions, they can only explain and probe most of the weak interactions, not all of them, and can’t explain any of the interactions that are mediated by the strong nuclear force. Attoseconds aren’t fast enough for all of particle physics; if we truly want to understand the Universe, we’ll have to get down to yoctosecond (~10^-24 second) precision. Here’s the science, and the inherent limitations, of that endeavor.

The speed of light is your friend

For most purposes that we use it for here on Earth, the speed of light is fast enough to be considered instantaneous. The first recorded, scientific attempt to measure the speed of light was performed by Galileo, who — in true Lord of the Rings/Beacons of Gondor fashion — sent two…