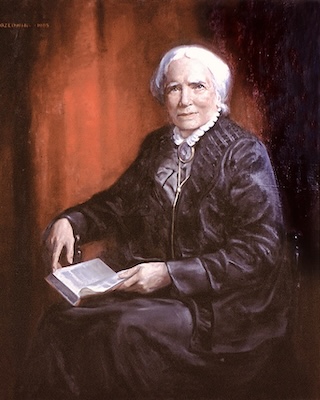

This month marks the 175th anniversary of Elizabeth Blackwell’s graduation from medical school, making her the first woman to be registered to practice medicine. Read more about her achievements in the field of public health.

As we strive to realize equality of opportunity across race, gender, and other categories, Americans can learn from those who came before us. Elizabeth Blackwell defied the norms of yesterday to empower the women of tomorrow. The first woman to earn a medical degree in the United States, she also became the first woman registered to practice medicine in on the Medical Register of the General Medical Council for the United Kingdom. Later she helped to open the first medical college for women in the US, where she promoted hygienic medical practices.

Blackwell’s Quaker and Abolitionist Upbringing

Blackwell grew up as the third of nine children in a middle-class Quaker family in England. Her father, Samuel Blackwell, supported the family by operating sugar refineries; yet he challenged the norms of the sugar industry by questioning its reliance on slave labor. After emigrating to the United States in 1832, he started a new sugar refinery and had many interactions with sugar plantation owners in the South and Caribbean. He would be quoted in Thomas Weld’s “American Slavery As It Is” (1839), explaining how sugar planters worked their enslaved to death because it was economical to replace them with new African captives. In a letter to his family in England he wrote, “The Spirit of slavery blackens and curses everything here morally and politically, and I fear will work like a canker until perfect rottenness will be the end and ruin of these states.” He and his family joined the Anti-Slavery Society of New York, meeting such notable abolitionists as William Lloyd Garrison, who, as Blackwell wrote in her autobiography, “was a welcome guest in our home.” Samuel Blackwell’s willingness to defy societal norms would be passed on to his offspring.

Samuel Blackwell and his wife, Hannah, were also progressive in allowing their daughters to be just as educated as their sons. This would have a profound impact on the course of Elizabeth Blackwell’s life. After her father’s untimely death, the family moved from New York to Ohio. The three older sisters (including Elizabeth) started a boarding school for girls to help provide for the family. In 1844, Elizabeth became head teacher at a schoolhouse in Henderson, Kentucky. It was here that she came to face to face with the harsh realities of slavery. “I dislike slavery more and more every day . . . . To live in their midst, utterly unable to help them is to me dreadful.” Returning to Ohio to live with her family, Blackwell cultivated friendships with prominent reformers who lived nearby, in the Walnut Hills suburbs of Cincinnati: the family of Lyman Beecher, President of Lane Seminary; seminary professor Calvin Ellis Stowe, and eventually Lucy Stone, an abolitionist and women’s rights advocate, who married Blackwell’s brother Henry. Stone was the first woman from Massachusetts to graduate from college. She and Henry collaborated on the Marriage Protest in May 1855.

Decision to Earn a Medical Degree

Working in medicine would only become an interest to Blackwell when a family friend, Mary Donaldson, turned ill. Blackwell went to visit Mary, dying of what was probably uterine cancer, who confided in Blackwell her wish for a woman doctor, to spare her of the shame of being examined and treated by men. As Blackwell wrote, Mary “died of a painful disease, the delicate nature of which made the methods of treatment a constant suffering to her.” The idea of becoming a doctor actually repulsed Blackwell. She wrote, “I hated everything connected with the body, and could not bear the sight of a medical book.” But the idea was planted in her head, and she could not shake it. The feeling of fulfillment in helping others appealed to her, as did the notion of being fully committed to something. Blackwell would now commit herself to being the first female doctor.

However, in 1845, there were no medical schools open to women. Blackwell wrote to every family doctor known to her family seeking advice on what steps to take. Some dismissed her idea outright. Others wrote more kindly, advising that it would be nearly impossible for her to be accepted into a medical school. Finding a new teaching job in Asheville, North Carolina, Blackwell studied with the school’s principal, Reverend John Dickson, who had worked previously as a doctor. In 1847, she moved to Charleston, where she taught music while studying privately under Dr. Sam Dickson, brother to John Dickson and a professor at the local medical school. She studied Greek and read all the medical books that Dr. Dickinson provided.

Having worked to save money, studied on her own and under the tutelage of qualified doctors, Blackwell decided in 1847 to apply to medical schools. She wrote to more than twenty, and was met with a resounding “No.” Women were thought to lack the intelligence to be a doctor, and to be too delicate for the sight of blood.

Defying Prejudice to Gain Medical Training

On October 20, 1847 the Dean of the Geneva Medical School in upstate New York wrote that the students and faculty had agreed to admit Blackwell as a student. He enclosed a resolution from the students which said, “That one of the radical principles of a Republican Government is the universal education of both sexes; that to every branch of scientific education the door should be open equally to all; that the application of Elizabeth Blackwell to become a member of our class meets our entire approbation.”

Despite having agreed unanimously to admit Blackwell, the students actually did not want her there. She did not make friends with other students. At times, her professors would discourage her from attending lectures showing the male body or the reproductive systems. Yet Blackwell was studious and undeterred despite whatever obstacle she was faced with. She wrote a note to a particular Professor Webster about the need for her to attend these lectures, and he relented.

On January 23, 1849 Blackwell graduated from Geneva Medical School at the top of her class. A townsperson in the audience at the commemoration, Margaret Munroe Delancey, wrote to her sister Josephine about the ceremony that “the ladies carried the day!”

After graduation, Blackwell wanted to pursue a career as a surgeon, and that meant more schooling. She hoped to take a residency at La Maternité in Paris. Yet even her diploma from Geneva Medical College did not suffice to allow her access. She was relegated to midwifery duties. It was here, while treating an infant with opthalmia, that she accidentally sprayed her own face with contaminated fluid, causing her to lose sight in her left eye. This incident, she later wrote, ended her dreams of becoming a surgeon, “for the condition of the affected organ entirely prevented that close application to professional study which was needed. Both anatomical and surgical work were out of the question.” In 1850, Blackwell returned to London to study at St. Bartholomew. While there she focused on diagnosing and studying cases presented.

Blackwell’s Contributions to Medicine

By the summer of 1851, she had returned to New York and was in the process of setting up her own practice. The next obstacle in her way was the refusal to rent her rooms. Finally, she found rooms to rent but could not advertise in front of the building. She placed advertisements in the New York Tribune but did not see many patients. By 1852, she started to lecture to girls and women about health. She would go on to publish these lectures in a book, The Laws of Life with Special Reference to the Physical Education of Girls. With this following, she was able to create a small family practice which would turn into a larger practice, a dispensary offering outpatient medicine.

Things began to change when Blackwell’s sister Emily and their friend Marie Zakrzewska, a German immigrant, obtained medical degrees. In May 1857, they were able to open a hospital on Bleeker Street in New York, the New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children. It was here the women would start to train nurses as well. The hospital served some of the neediest population of New York City. In 1865, the hospital applied for permission to open a medical school and began to raise capital. In November of 1868, the Women’s Medical College of the New York Infirmary opened.

Elizabeth Blackwell became the school’s first professor of hygiene, giving it equal importance to other subjects. Medical training prior to this ignored hygiene, leading to countless infections and deaths. It took female pioneers like Florence Nightingale and Elizabeth Blackwell to prioritize cleanliness, ample light and fresh air in patient care. The Women’s Medical school stayed open until 1899, when Cornell started allowing women to study there.

“It is not easy to be a pioneer—but oh, it is fascinating. I would not trade one moment, even the worst moment, for all the riches in the world.” Elizabeth Blackwell had a dream and determination. Whatever obstacle was in her way, she found a way to adapt and get around it. Blackwell laid the foundation for all women who want to pursue a medical career, while providing a powerful example of perseverance in the face of discrimination.

Lauren Goepfert is a student in the Master of Arts in American History and Government program at Ashland University. Named the 2018 Madison Fellow for the state of Florida, she now teaches at Longwood High School on Long Island, NY.