(RNS) — The Rev. Jacqui Lewis, a New York City pastor, and the Rev. Shannon Daley-Harris, an associate dean of a seminary in the city, teamed up to reach young readers with a colorful Bible focused on justice and love.

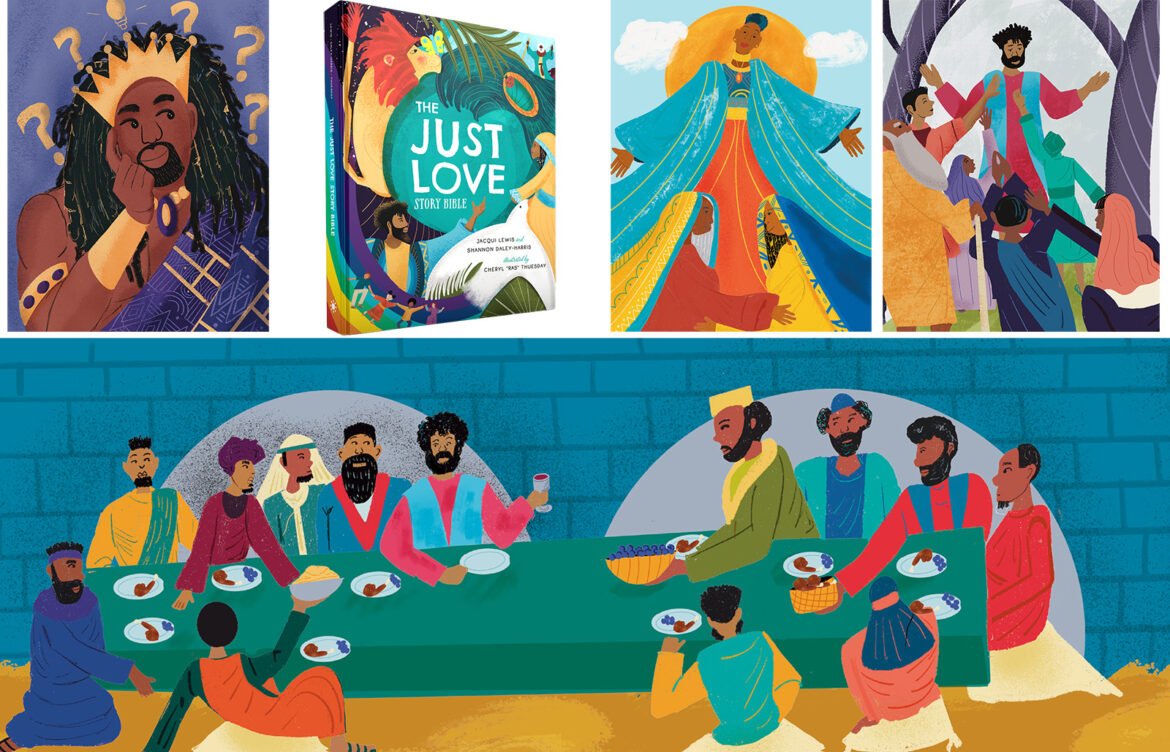

“The Just Love Story Bible,” released last month by Beaming Books, a children’s book publisher, follows a theme Lewis has long preached at Middle Collegiate Church, a multiethnic congregation in Manhattan’s East Village affiliated with the United Church of Christ.

“This feels to me like a ubiquitous call to make ‘just love’ the window through which Christianity happens,” Lewis, 66, said in an Oct. 8 interview with Daley-Harris, 60, associate dean of Auburn Theological Seminary in Morningside Heights.

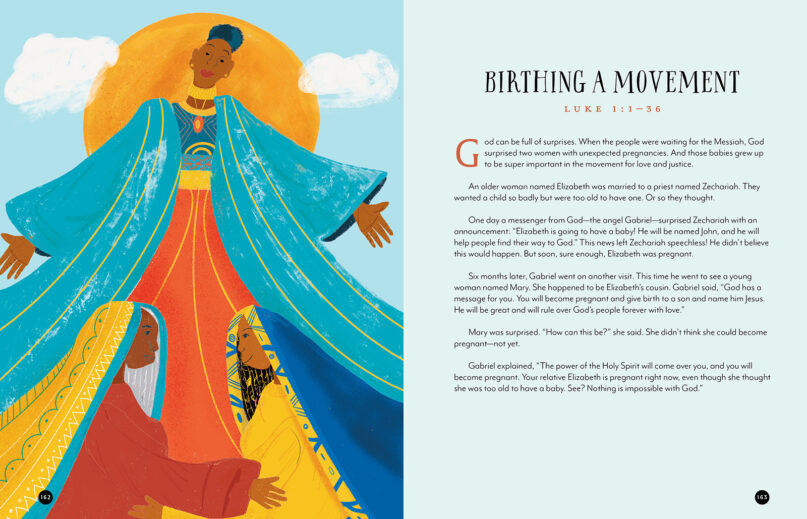

Daley-Harris said they chose to include 52 stories — 26 from each testament — to be read once a week for a year. Each week, they hope children flip through the 295-page book with colorful illustrations by artist Cheryl “Ras” Thuesday featuring a white-bearded Abram and Jesus with a textured Afro.

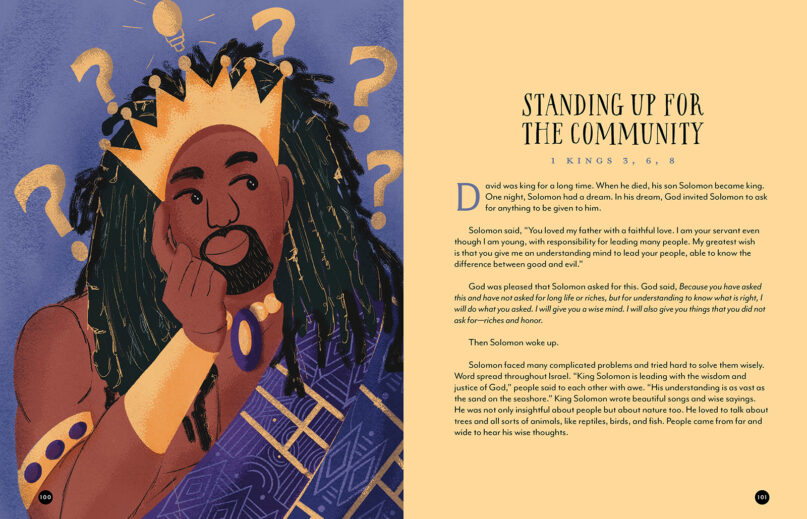

“When you’ve only got 26 stories and your commitment is to telling the big story of God’s love and justice, it really makes you think, what are the stories that carry the most important, most central messages about God’s love and justice?” Daley-Harris said.

Lewis and Daley-Harris, both Presbyterian Church (USA) ministers, held a book launch event at Lewis’ church in early September, and soon Daley-Harris expects to introduce it to seminary fellows who can use it to “move worship to a fully intergenerational experience where no child is ever sent out of the sanctuary,” she said.

RELATED: New illustrated story Bible ‘a portable cathedral’ for children

“The Just Love Story Bible” illustrator Cheryl “Ras” Thuesday, from left, and authors the Rev. Jacqui Lewis and the Rev. Shannon Daley-Harris during a launch party for the book. (Photo by Patrick Mulcahy)

The co-authors spoke with Religion News Service about how they split their work on the project, what they hope it will teach children and who they think is most likely to read it. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why did you create “The Just Love Story Bible”?

Lewis: I was approached by Beaming Books a while ago about doing an interfaith project. And as time went on, it seemed right to do a Christian book given all the meshugaas (a Yiddish term for madness) in the world about what Christianity is or isn’t. Shannon has all of these gifts from writing liturgy for the Children’s Defense Fund, and she’s got a really strong sense of the Hebrew Bible. Our agenda is teach young people a theology of love and justice that we don’t have to unlearn because they understand from the beginning what this faith is really about.

What age group are you hoping to reach?

Daley-Harris: It’s for kids age 4 to 10. Our hope is to take seriously children’s capacity to think theologically and wonder and bring curiosity and imagination and to present a story Bible that can grow with them. It’s OK to actually tell kids from the get-go: Some of these stories are about true people and things that really happen, and some of them are made-up stories, but they’re in there because they can still teach us true things about God. You can tell the story of Jonah and the whale and still let kids at all these different developmental levels get into it imaginatively to extract the true lessons about us as God’s people, without feeling like they have to — pardon the pun — buy the swallowed-by-whale thing, hook, line and sinker.

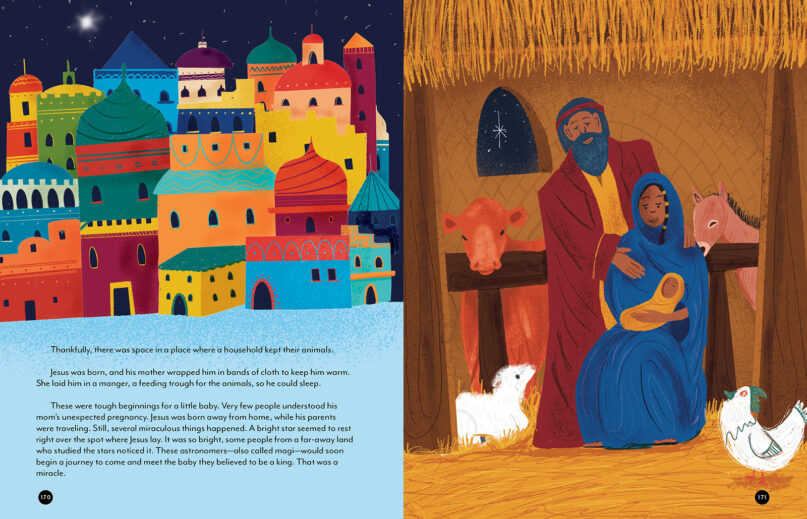

Excerpt from “The Just Love Story Bible.” (Image courtesy of Beaming Books)

Can you talk about the art in the book?

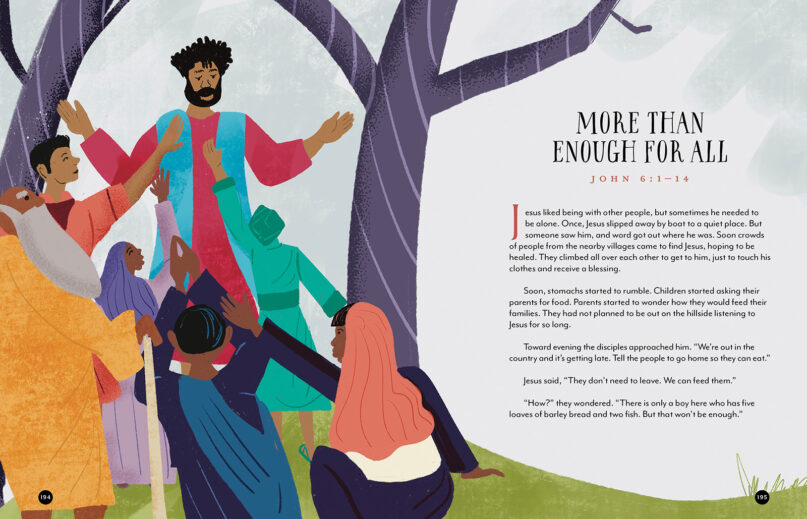

Lewis: It is the most gorgeous rainbow of faces. When we talk about what children can do and how they can be activists, or how they can be revolutionary lovers, that looks like a rainbow of people. But the biblical characters mostly look Black and brown and caramel, which is what we would really experience in the region. In the world where children have been exposed to white characters in Bibles for as long as Christianity has been Christian, now white children, I imagine, looking in this Bible and seeing brown people and thinking to themselves, “Oh, brown people belong to God, too.”

One of you wrote the Old Testament and the other wrote the New Testament. What was most challenging about working on each of them, especially for younger readers?

Daley-Harris: Frankly, the discipline of 300 to 500 words to tell a story in a sort of theologically responsible way. And knowing this book will be for some kids who go to church every Sunday with their families, and some who have never been before and are interested in what it’s all about. Some of them, there is enough dialogue and detail in the text to stay quite close to what we find in Scripture. And then others are almost more like modern midrash — that wonderful Jewish tradition of imagining a text, imagining what wasn’t said, what might have come before or come after. We say this explicitly in one of the introductions: How might the story have been told differently by somebody else who was there?

Lewis: The New Testament is like this: There was a birth, a death and a resurrection. And (we) want to stay, in a way, orthodox enough that parents who really care about those stories will pick up the Bible and read it, and then we can stretch them, which was my hope and challenge. And when we got to resurrection, I went all the way philosophical, “some people like Plato think… ” and “some people like Aristotle think… ,” to just introduce our faith also includes doubt and the possibility of having a hermeneutic of suspicion. Did that happen? For me, it matters more that children know that love never dies, so that’s where I landed.

Excerpt from “The Just Love Story Bible.” (Image courtesy of Beaming Books)

Does that mean this Bible may only be for people who might consider themselves, as you do, progressive, rather than for conservatives who might say the Bible is the inerrant word of God or a holy book without error?

Daley-Harris: There will be a group of sort of literalist or fundamentalist folks for whom this isn’t a welcome resource. But it’s been really interesting to see the reception from not just folks who are raised progressive, but those who are raised in a tradition that no longer fit them, who did grow out of a theology and are looking for one that they can grow into and grow with alongside their children.

In your summary of the fifth chapter of Matthew, you restate Jesus’ words about the ease of loving friends but the importance of loving enemies as well. And you note, “Whew. Loving people can be hard work.” How does that discussion apply to these days of polarization as adults read these words to children?

Lewis: I don’t think when we were working on the book four-and-a-half years ago we would have known just how timely this is for all Christians across the spectrum of conservative and liberal to pick up on that question. Faith is a leap. Faith is a journey.

Excerpt from “The Just Love Story Bible.” (Image courtesy of Beaming Books)

In your summary of Leviticus 19, you include the divine lesson “You shall love immigrants as yourself, for you were immigrants in the land of Egypt. I am your God.” Why did you choose that wording rather than that of other translations that have used “stranger” or “foreigner”?

Daley-Harris: Whatever the language is, the heart, essence and message is, “we’re all newly arrived at this place.” What does it mean to not try to slam the door behind you, but to really use that lived experience to create some empathy for those who are experiencing it anew? Other than our Indigenous friends who are still living in the United States, we’re all immigrants, ancestrally and historically, to this place.

You include stories about women in both testaments, such as the Book of Numbers’ account of the sisters who sought to keep their family land after their father, Zelophehad, died, and women who followed Jesus along with the 12 disciples. Is there a particular message you hope to bring to children about women in Jesus’ time and earlier?

Lewis: Absolutely: that Jesus was a feminist, and maybe there wasn’t language for that then, but he was a culturally Jewish man, a rabbi, who came to understand that he could relate to women differently than the culture around him. He engaged them. He drew them in. And I think those lessons are super important in this modern context. When Shannon and I say, we don’t want children to learn something they have to unlearn, we don’t want them to learn patriarchy from this story Bible.

Excerpt from “The Just Love Story Bible.” (Image courtesy of Beaming Books)

RELATED: New children’s Bibles rethink how Christians share old, old story with young readers