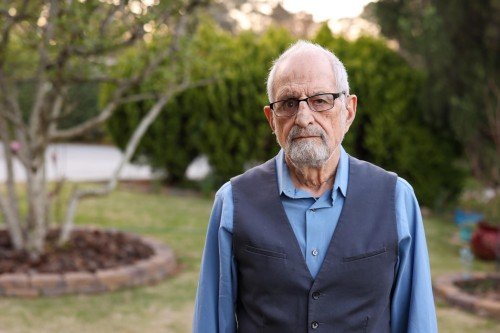

(43/54) “Thirty years earlier we’d sworn an oath, to give our lives for Iran. I considered it. There was one parliamentarian who fled to the mountains and died fighting. Even with one eye, I was still a good shot. I could have made a stand. But if I gave my life, it would have to be in exchange for something. Thousands of people were dying at the time, and nothing was changing. The clerics only grew more powerful. The same slogans were being chanted in the streets. Our freedoms continued to be taken away. And then there was Mitra and the children. I couldn’t leave them behind. But with each week came more bad news: another colleague killed, another one arrested. My friends started encouraging me to leave the country, but I wouldn’t consider it. I had promised myself when I came home from Germany that I’d never leave Iran again. But even if I had wanted to, it wasn’t possible. I didn’t have a passport. I was on a list of people who were not allowed to leave the country. One afternoon we received a visit from a former colleague. He sat Mitra and I down in the living room, and he told us that he’d discovered a way to leave Iran through the Turkish border. There was a powerful family there that was known to oppose the regime. He said that the checkpoints weren’t stopping cars with families. So if Mitra rode to the border with me, I’d be able to walk the rest of the way on foot. He turned to Mitra, and said: ‘This is his final chance. If he is killed, never say that his friends abandoned him. We’ve done everything we can to convince him, so now it’s up to you.’ When he was finished, Mitra turned to me and said: ‘You must go.’ And Mitra’s word is law. We set out early in the morning. It was an eight-hour drive to the Turkish border. The entire ride was spent in silence. She kept her emotions hidden. I was a tsunami of tears. We kissed goodbye in Salmas. There was a statue of Ferdowsi in the main square.”

سی سال پیش سوگندی یاد کرده بودیم که جانمان را برای ایران ببازیم. به آن اندیشیدم. نمایندهی مجلسی بود که به کوهستان رفته و در جنگ و گریز جان باخته بود. با داشتن یک چشم، هنوز تیرانداز خوبی بودم. میتوانستم در درگیری ایستادگی کنم. ولی باید چیزی در برابر جان باختن بدست آورد. میدیدم هزاران تن به خاک افتادهاند. تنها بر قدرت روحانیون روز به روز افزوده میشد. همان شعارهای یکسان در خیابانها سرداده میشدند. آزادیهایمان را یکی پس از دیگری میگرفتند. با میترا و فرزندانم چه میکردم. او را نمیتوانستم بی پشت و پناه بگذارم. برخی دوستان مرا به ترک کشور میخواندند. جان بیبها بود. دوستانم یکی پس از دیگری دستگیر میشدند. یکبار هم به گزینهی رفتن نیندیشیده بودم. نه، حتا یکبار. گذرنامه هم نداشتم. نامم هم در لیست ممنوعالخروجها قرار گرفته بود. یک روز پس از نیمروز، دوست بس ارجمند سالهایم به خانهمان آمد. به گفتوگو نشستیم. گفت که مسیری برای ترک ایران از راه مرز ترکیه یافته است. خانوادهای پرنفوذ در آن ناحیه زندگی میکرد که مخالف رژیم بود. پلیس راه خودروهایی را که با خانواده سفر میکردند نگه نمیداشت. اگر میترا با من تا شهر مرزی میآمد، میتوانستم بازماندهی راه را پیاده بپیمایم. او به میترا گفت که این واپسین بخت است. گفت: “ما تمام تلاشمان را برای راهی کردنش انجام دادهایم. اکنون دیگر به شما بستگی دارد. اگر ماند و کشته شد، هرگز نگویید که دوستانش او را تنها گذاشتند.” میترا در خاموشی گوش فرا داد. هنگامی که سخن دوستم به پایان رسید، میترا رو به من کرد و گفت که باید بروی و سخنش قانون بود. سپیدهدم راه افتادیم. سراسر راه را در خاموشی گذراندیم. او احساساتش را پنهان میکرد. من توفان اشک بودم. در شهر سلماس با بوسهای یکدیگر را بدرود گفتیم. در میدان اصلی شهر تندیسی از فردوسی برپا بود