By the end of 1967, almost 20,000 Americans had died in Vietnam and the total number of American troops had increased to over 500,000, but progress in the war was hard to see. The November 11, 1967 issue of the New York Times reported on a Gallup poll that found 59 percent of Americans in favor of continuing the war in Vietnam. Of those who wanted to continue the war, 55 percent wanted a military effort greater than President Lyndon Johnson was willing to make. Seven percent even supported the use of nuclear weapons. Thirty-five percent wanted a decrease in the war effort, while only ten percent wanted immediate withdrawal. The polling data and Johnson’s discussions with members of Congress and some members of his administration suggested to him that support for his conduct of the war was slowly ebbing away.

In response, Johnson orchestrated a campaign to build support for his war. He brought military commanders home from Vietnam, who spoke of light at the end of the tunnel in their public appearances, and had administration officials give similarly optimistic speeches, while he himself made a series of appearances and speeches across the country. As Johnson’s public relations campaign unfolded, the North Vietnamese planned a major offensive in the south. Like many in the United States, the North Vietnamese leadership were frustrated that the war was not progressing as they had hoped it would. They therefore decided to undertake a General Offensive/General Uprising. Using North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong troops, as well as guerillas and terrorists, the North hoped to deliver a decisive blow. It would lead the people of South Vietnam to rise in support of the North, the Army of South Vietnam to desert or defect, and the government of South Vietnam to collapse. To support the offensive, the North increased the infiltration of personnel and supplies into the South, including through the port of Sihanoukville in supposedly neutral Cambodia. The North also received more aid and assistance from the Soviet Union and China. It renewed efforts to secure its home front through a purge of party officials and increased efforts against counter-revolutionaries, while it sought to disguise its intentions by launching peace feelers. Toward the close of 1967, it announced a truce for the Tet or lunar holidays that would take place in January.

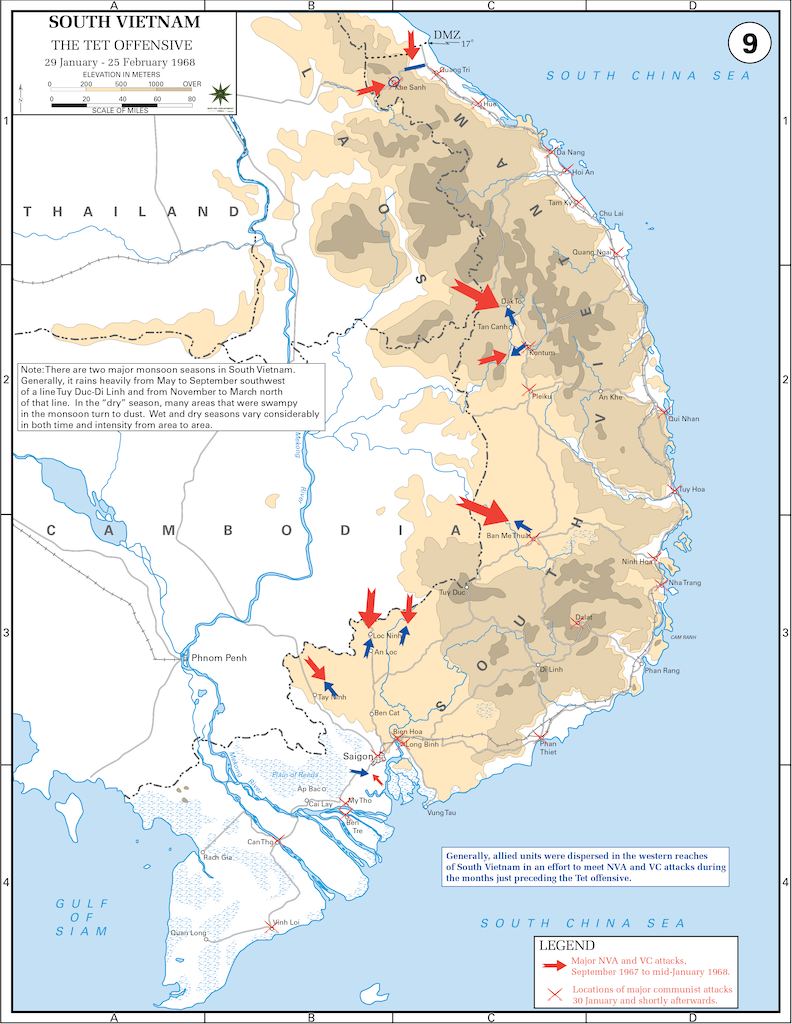

The General Offensive began with attacks throughout the South at the end of January. The communists enjoyed initial success, even penetrating the U.S. embassy grounds in Saigon. Viet Cong main force and North Vietnamese Army units attacked provincial capitals and major cities, as well as U.S. and South Vietnamese bases, camps, and airfields. In cities and villages, the Viet Cong assassinated government officials. United States and South Vietnamese forces rallied, however, and turned the North’s initial success into defeat. The fighting devastated the Viet Cong and inflicted heavy casualties on North Vietnamese forces. Some of the most intense fighting occurred in Hue, a provincial capital in northern South Vietnam, where the house-to-house fighting continued through February. After the communists were driven out of Hue, evidence emerged of a massacre of several thousand people: government officials, other civilians, including foreign nationals, and South Vietnamese soldiers home for the Tet holiday. Smaller massacres had occurred in other places. Many civilians were killed during the General Offensive or Tet Offensive, as it was called by the Americans. Tens of thousands were made refugees.

Although a military defeat for the North Vietnamese, the offensive brought them a political victory in the United States. Trying to build support for the war, the Johnson administration had done nothing to prepare the American public for the coming offensive, of which it had been warned in advance by U.S. intelligence. But senior officials at the Embassy in Saigon and in Washington were skeptical of the reports. As an official military history put it, “They believed, correctly as it turned out, that a nationwide offensive was beyond North Vietnamese and Viet Cong capabilities.” Reports and images of the fighting shocked Americans. One showed the national chief of police on a street in Saigon summarily executing a Viet Cong suspected of having killed a South Vietnamese officer and his family. Events in Vietnam did not cause support for the war to collapse, but they did decrease support for Johnson. On March 12, 1968, Johnson managed only a narrow victory over McCarthy in the New Hampshire primary. Robert Kennedy entered the race four days later.

The Tet offensive also caused a reconsideration of the strategy in Vietnam among key officials in the Johnson administration. The military wanted to exploit communist losses by going on the offensive again; it requested the addition of slightly more than 200,000 troops. Civilians in the Pentagon and the White House raised doubts about the troop request and the strategy it was meant to serve. The new Secretary of Defense, Clark Clifford, was opposed to the military’s plans. He foresaw only more casualties, with no end in sight. He suggested to Johnson a much smaller troop increase—about a tenth of what the military had requested—coupled with pressure on the South Vietnamese to do more.

Johnson gave a major speech on the war on March 31, 1968. He explained that the Tet offensive had failed in its objectives but that the communists had not given up their effort to conquer the South. He renewed the offer of negotiations, ordering a halt to bombing except in the area immediately above the demilitarized zone, where North Vietnamese main forces were still staged for attack. He detailed the steps the South Vietnamese would take to increase their role in the war. He reported that he was sending only support troops to Vietnam (a smaller number even than Clifford had recommended) and that the troop level would remain where it had been, at 525,000. He reiterated his call for a tax increase, explaining that deficit spending was straining the American economy. (Inflation reached 3 percent in 1967, rising from a very low level.) America’s objective was what it had always been, “peace and self-determination,” as the best way to protect America’s interests. He concluded with the shocking announcement that “I shall not seek, and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your President.” Johnson was exhausted and saw little chance that he would achieve much, if anything, even if he won re-election.

Nothing came of Johnson’s peace initiative. The fighting continued. In fact, more Americans died in Vietnam in 1968—16,899—than in any year of the war. The bombing resumed. The character of the war had changed, however. Viet Cong losses during Tet among political cadre, guerillas, and main force units was so great, and the violence they had inflicted on civilians so marked, that they never fully recovered, militarily or politically. As a consequence, South Vietnamese and American efforts had greater success. South Vietnamese control of the countryside increased and continued to increase in subsequent years. Yet in America, ironically, public support for the war continued to decline. By the end of 1968, total dead from the war reached 35,540. Riots in Newark and Detroit in the summer of 1967 and in Washington, D.C. and during the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in 1968 added to a sense of crisis and disintegration.

David Tucker is General Editor of TAH publications. He is writing one of TAH’s narrative histories, America during the Age of the Vietnam War, from which this post is excerpted.