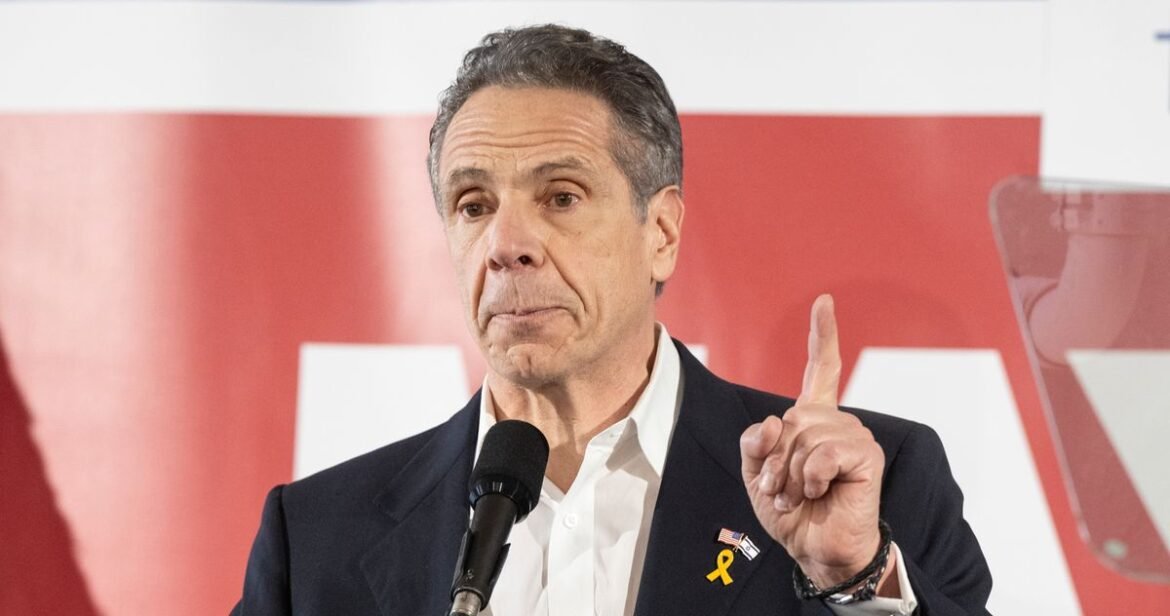

Photo: Lev Radin/Pacific Press/LightRocket via Getty Images

There is only one great question hanging over this deeply unlikely Democratic primary for mayor of New York City: Can Andrew Cuomo run out the clock?

The former governor, bursting into a union hall a little over a week ago, put to rest many months of speculation and upended a race that already hinged on the unpredictability of Eric Adams, the once-indicted and historically unpopular incumbent. Almost no one in New York politics believes Adams, who now carries a catastrophic approval rating of 20 percent, can win again. He is set to become the city’s first one-term mayor in 30 years. More than a few politicos are settling into the reality that Cuomo, who resigned in disgrace a little over three years ago, might just overpower the field with his universal name recognition and deep executive experience — the sort that the electorate might be pining for after the chaos of the Adams years. Cuomo is expected to play it relatively safe, mostly avoiding a relentless and adversarial city press corps and letting his well-funded super-PAC bludgeon his rivals into submission.

It’s still a long way between now and June 24. Every Democrat running in the race, Adams included, will have one sole focus: dragging Cuomo’s poll numbers down. The various Cuomo antagonists — the operatives working on a significant anti-Cuomo PAC and the candidates themselves — believe there are vulnerabilities that can be exploited. There are the sexual-harassment scandals and the fact that Cuomo so aggressively battled back against the young women who accused him, dragging them through court. There’s his fraught decadelong tenure as governor, which had both undeniable successes (the rehab of La Guardia Airport) and ugly failures (the Buffalo billion corruption). His stewardship of the pandemic, beginning with how his administration tabulated deaths at nursing homes and his decision to accept more than $5 million in 2020 to write a memoir, will come in for far greater scrutiny.

Who can beat Cuomo is the easy enough rejoinder to anyone who points out his myriad flaws or the softness of his polling lead. No one, for now, comes very close. Brad Lander, the progressive city comptroller, is aiming to be the primary alternative to Cuomo and could find a way there with strong fundraising and a growing list of endorsers. His major challenge will be winning over voters beyond his affluent Brooklyn base, just as Scott Stringer, his predecessor, must try to corral support beyond the West Side of Manhattan, where he’s still well known. Zellnor Myrie, a young Afro-Latino state senator from Brooklyn, might have a higher ceiling than either man (or socialist assemblyman Zohran Mamdani, who came in a distant third to Cuomo in a recent Quinnipiac poll), but he’s yet to break out from the pack. All four of these Democrats have qualified for millions in public matching funds, so they must be regarded as the serious contenders in what will be an expensive, nasty race.

The panic over the possible inability of Lander-Stringer-Myrie-Mamdani to stop Cuomo has prompted Adrienne Adams, the City Council Speaker, to enter the fray. A soft-spoken and well-regarded legislative leader (who is not related to the mayor), she has a base of middle-class Black supporters in southeast Queens who are reliable primary voters. Urged to run by attorney general Letitia James, who would have been a formidable candidate herself if she chose to run, Adrienne Adams could steadily rise if large labor unions coalesce around her and she’s successful at netting media attention.

Her major challenge is fundraising. She has a little more than $200,000 in her war chest and will have to play catch-up with the Democrats who’ve already banked multiple millions and will be ready, before her, to build out large field operations and run television ads. Adrienne Adams probably should have been a candidate three or four months ago. Had she launched in the fall, she would have qualified for public matching funds by now and been on an inside track to win over a wide array of elected officials and unions. Instead, she’ll be fighting for oxygen, and she’ll need a clear message to distinguish herself from a large field training their fire on Cuomo. If she wins, she’d be New York’s first female mayor, and perhaps that history-making potential will excite some of the electorate.

No one quite knows how ranked-choice voting will impact the race, and it will be only the second mayoral primary with RCV. In 2021, Kathryn Garcia finished third among first-place votes and then, once all the choices were tabulated — New York Democrats can rank up to five candidates — Garcia surged, coming within 10,000 votes of defeating Eric Adams. The lesson was twofold: It still pays to finish first, since Adams did win, but it’s very possible to rise if you’re appealing to a broad range of people. There are several RCV Cuomo theories. One school of thought is that his superior name recognition will carry the day and he’ll show up on many ballots in many different neighborhoods, whether it’s in the Latino areas of the Bronx or the Black enclaves of Queens or Orthodox Jewish Brooklyn. There’s a multiracial coalition for Cuomo to build that could be larger than the one Adams assembled in 2021.

But RCV can also punish polarizing candidates. Andrew Yang, the front-runner four years ago, was dropped from a lot of ballots. Progressives are floating a new slogan, DREAM (Don’t Rank Eric or Andrew for Mayor), and it’s easy enough to see such a movement take off in large swaths of left-leaning Brooklyn and Queens. If the Working Families Party wants to get serious about growing their influence in municipal politics again, they can fund a multimillion-dollar initiative focusing only on convincing voters to leave Cuomo off their ballots. As Election Day draws closer, the various non-Cuomo candidates could form alliances and cross-endorse. There’s evidence that a last-minute Garcia-Yang cross-endorsement four years ago netted Garcia votes from Yang supporters and drew her closer to victory.

What’s been most intimidating is Cuomo’s polling. His actual campaign rollout has been a bit pedestrian — and it’s hard to tell, for now, what that truly means. His launch video was an unwieldy 17 minutes and was ruthlessly mocked online. His endorsement roster is still shallow for a vaunted front-runner, featuring only a handful of sitting elected officials and labor unions not known for swaying citywide primaries. It is possible that his roster could grow quickly if no one else seems to be gaining traction. Major unions like 32BJ SEIU, the building-workers union, and the Hotel and Gaming Trades Council might close ranks around Cuomo, prompting other institutional forces to join him. He could very well be an unstoppable political battleship. We’ll know in the spring whether he’ll take on any water.